Indian Massacres Around Franktown, Pennsylvania

OLD INDIAN TOWN OF FRANKSTOWN — INDIAN BURIAL-PLACES — MASSACRE OF THE BEDFORD SCOUT, E

Frankstown is probably the oldest place on the Juniata River—traders having mentioned it as early as 1750. The Indian town was located at the mouth of a small run, near where McCune's Mill now stands, and at one time contained a considerable number of inhabitants. The Indian name of the place was Assunepachla, which signifies a meeting of many waters, or the place where the waters join. This would seem to be an appropriate name, since, within a short distance of the place, the river is formed by what was then known as the Frankstown Branch, the Beaver Dam Branch, the Brush Run, and the small run near McCune's Mill.

The name of Frankstown was given it by the traders. Harris, in his report of the distances between the Susquehanna and the Alleghany, called it "Frank (Stephen's) Town." The general impression is that the town was named by the traders in honor of an old chief named Frank. This, however, is an error. It was named after an old German Indian trader named Stephen Franks, who lived contemporaneously with old Hart, and whose post was at this old Indian town. The truth of this becomes apparent when we remember that the Indians could not pronounce the r in their language; hence no chief was likely to bear the name of Frank at that early day. Old Franks, being a great friend of the Indians, lived and died among them, and it was after his death that one of the chiefs took his name; hence arose the erroneous impression that the name was given to the town in honor of the chief.

How long Assunepachla was an Indian settlement cannot be conjectured, but, unquestionably, long before the Indians of the valley had any intercourse with the whites. This is evidenced by the fact that where the town stood, as well as on the flat west of the town, relics of rudely-constructed pottery, stone arrow-heads, stone hatchets, &c., have repeatedly been found until within the last few years.

The use of stone edge-tools was abandoned as soon as the savages obtained a sight of a superior article,—probably as early as 1730. The first were brought to the valley by Indians, who had received them as presents from the proprietary family.

It is stated that the first brought to Assunepachla cost a special trip to Philadelphia. Three chiefs, having seen hatchets and knives at Standing Stone, were so fascinated with their utility that they resolved to have some. Accordingly they went to work at trapping; and in the fall, each with an immense load of skins, started on foot for Philadelphia, where they arrived after a long and fatiguing march. They soon found what they wanted at the shop of an Englishman; but, being unable to talk English, they merely deposited their furs upon the counter and pointed to the tomahawks and knives. This indicated trade; and the Englishman, after a critical examination of their skins, which he found would yield him not less than £100, threw them carelessly under the counter, and gave them a hatchet and a knife each. With these the savages were about to depart, well satisfied; but the trader suddenly bethinking himself of the possibility of their falling in with the interpreters, and their ascertaining the manner in which they had been swindled, called them back, and very generously added three clasp-knives and a quantity of brass jewelry.

With these they wended their way back, proud as emperors of their newly-acquired weapons. Never did chiefs enter a place with more pomp and importance than our warriors. The very dogs barked a welcome, and the Indians came forth from their wigwams to greet the great eastern travelers. Their hatchets, knives, and trinkets passed from hand to hand, and savage encomiums were lavished unsparingly upon them; but when their practicability was tested, the climax of savage enthusiasm was reached. The envied possessors were lions: they cut, hewed, and scored, just because they could.

But—alas for all things mutable!—their glory was not destined to last long. The traders soon appeared with the same kind of articles, and readily exchanged for half a dozen skins what the warriors had spent a season in trapping and a long journey to procure.

On the point of Chimney Ridge, near Wert's farm, below Hollidaysburg, was an Indian burial-place, and another on the small piece of table-land near the mouth of Brush Run. At both places, skeletons of mighty chiefs and all-powerful warriors have been ruthlessly torn from their places of sepulture by the plough, and many other relics have been exhumed.

The greater portion of the warriors residing at Frankstown went to Ohio in 1755, and took up the hatchet for their "brothers," the French, and against Onus, or their Father Penn. This act, the colonial government persuaded itself to believe, was altogether mercenary on the part of the savages. The real cause, as we have already stated, was the dissatisfaction which followed the purchase of the Juniata Valley by the Penns, for a few paltry pounds, from the Iroquois, at Albany, in 1754.

The town of Frankstown still continued to be a prominent Indian settlement until the army of General Forbes passed up the Raystown Branch when the spies sent out brought such exaggerated reports of the warlike appearance and strength of the army that the settlement was entirely broken up, and the warriors, with their squaws, pappooses, and movable effects, crossed the Alleghany by the Kittaning War-Path, and bade adieu to the valley which they were only too well convinced was no longer their own.

The remains of their bark huts, their old corn-fields, and other indications of their presence, were in existence until after the beginning of the present century.

On the flat, several white settlers erected their cabins at an early day, and a few near the old town, and others where the town of Frankstown now stands.

During the Revolution, as we have stated, a stable erected by Peter Titus was turned into a fortress. In summer, the location of the fort can still be traced by the luxuriant growth of vegetation upon it. This fort was called Holliday's Fort. The fort at Fetter's, a mile west of Hollidaysburg, was known as the Frankstown garrison. In those days there was no such place as Hollidaysburg, and the Frankstown district took in a scope of country which now serves for five or six very large townships; in short, every place was Frankstown within a radius of at least ten miles.

Holliday's Fort was a mere temporary affair; while the Frankstown garrison was a substantial stockade, manned and provisioned in such a manner that a thousand savages could by no possible means have taken it. It never was assaulted except upon one occasion, and then the red-skins were right glad to beat a retreat before they were able to fire a gun.

Near this fort occurred the massacre of the Bedford scout. This was unquestionably the most successful savage sortie made upon the whites in the valley during the Revolution; and, as some of the bravest and best men of Bedford county fell in this massacre, it did not fail to create an excitement compared to which all other excitements that ever occurred in the valley were perfect calms.

We shall, in the first place, proceed to give the first report of the occurrence, sent by George Ashman, one of the sub-lieutenants of the county, to Arthur Buchanan, at Kishicoquillas. Ashman says:—

Sir:—By an express this moment from Frankstown, we have the bad news. As a party of volunteers from Bedford was going to Frankstown, a party of Indians fell in with them this morning and killed thirty of them. Only seven made their escape to the garrison of Frankstown. I hope that you'll exert yourself in getting men to go up to the Stone; and pray let the river-people know, as they may turn out. I am, in health,

Geo. Ashman.

Of course Colonel Ashman was not near the place, and his despatch to Buchanan is, as a natural consequence, made up from the exaggerated reports that were carried to him at the instance of the affrighted people residing in the vicinity where the massacre occurred. The following is the official report, transmitted by Ashman to President Reed:—

Bedford County, June 12, 1781.

Sir:—I have to inform you that on Sunday, the third of this instant, a party of the rangers under Captain Boyd, eight in number, with twenty-five volunteers under Captain Moore and Lieutenant Smith, of the militia of this county, had an engagement with a party of Indians (said to be numerous) within three miles of Frankstown, where seventy-five of the Cumberland militia were stationed, commanded by Captain James Young. Some of the party running into the garrison, acquainting Captain Young of what had happened, he issued out a party immediately, and brought in seven more, five of whom are wounded, and two made their escape to Bedford,—eight killed and scalped,—Captain Boyd, Captain Moore, and Captain Dunlap missing. Captain Young, expecting from the enemy's numbers that his garrison would be surrounded, sent express to me immediately; but, before I could collect as many volunteers as was sufficient to march to Frankstown with, the enemy had returned over the Alleghany Hill. The waters being high, occasioned by heavy rains, they could not be pursued. This county, at this time, is in a deplorable situation. A number of families are flying away daily ever since the late damage was done. I can assure your Excellency that if immediate assistance is not sent to this county that the whole of the frontier inhabitants will move off in a few days. Colonel Abraham Smith, of Cumberland, has just informed me that he has no orders to send us any more militia from Cumberland county to our assistance, which I am much surprised to hear. I shall move my family to Maryland in a few days, as I am convinced that not any one settlement is able to make any stand against such numbers of the enemy. If your Excellency should please to order us any assistance, less than three hundred will be of but little relief to this county. Ammunition we have not any; and the Cumberland militia will be discharged in two days. It is dreadful to think what the consequence of leaving such a number of helpless inhabitants may be to the cruelties of a savage enemy.

Please to send me by the first opportunity three hundred pounds, as I cannot possibly do the business without money. You may depend that nothing shall be wanting in me to serve my country as far as my abilities.

I have the honor to be

Your Excellency's most obedient, humble servant,

George Ashman, Lieut. Bedford County.

It would appear that even a man holding an official station is liable to gross mistakes. In this instance, Ashman, who lived remote from the scene of the disaster, was evidently misled by the current rumors, and such he transmitted; for there are still persons alive, who lived at the time of the occurrence in the immediate vicinity, who pronounce Ashman's statement as erroneous, and who give an entirely different version of the affair.

The seventy Cumberland county militia, under strict military discipline, were sent first to Standing Stone, and afterward to Frankstown, early in the spring of 1781. They were under the command of Colonel Albright and Captain Young, and were sent with a view to waylaying the gaps of the Alleghany Mountains, and preventing any savages from coming into the valley. Instead of doing so, however, they proved themselves an inefficient body of men, with dilatory officers, who chose rather the idle life of the fort than scouting to intercept the savages. In fact, these men, in the service and pay of the Supreme Executive Council of the State to protect the frontier, were never one solitary cent's worth of advantage to the inhabitants. Such a force, one would suppose, would have inspired the people with confidence, and been fully able to cope with or repel the largest war-party of savages that ever trod the Kittaning War-Path during the Revolutionary struggle.

Notwithstanding the presence of this large body of men, stationed as it were almost at the mouth of the gap through which the Indians entered the valley, the depredations of the savages were almost of daily occurrence. The inefficiency of the Cumberland militia, who either could not or would not check the marauders, at length exasperated the settlers to such an extent that they resolved to form themselves into a scouting party, and range through the county for two months.

This project was favored by Colonel Ashman, and he agreed to furnish a company of rangers to join them. The enrolment of volunteers by Captain Moore, of Scotch Valley, assisted by his lieutenant, a Mr. Smith, from the vicinity of Frankstown, proceeded; and on the second of June, 1781, these men met at Holliday's Fort, then abandoned for want of provisions. There they were joined by the rangers, under command of Captain Boyd and Lieutenant Harry Woods, of Bedford, but, instead of there being a company, as the volunteers were led to expect, there were but eight men and the two officers above named.

From Holliday's Fort they marched to Fetter's, where they contemplated spending the Sabbath. It was their intention to march through the Kittaning Gap to an old State road, (long since abandoned,) from thence to Pittsburg, and home by way of Bedford.

While debating the matter and making the necessary arrangements, two spies came in and reported that they had come upon an Indian encampment near Hart's Sleeping Place, which had apparently been just abandoned, as the fire was still burning; that, from the number of bark huts, the savages must number from twenty-five to thirty.

This raised quite a stir in the camp, as the scouts evidently were eager for the fray. The officers, who were regular woodsmen, and knew that the Indians would not venture into the settlement until the day following, were confident of meeting them near the mouth of the gap and giving them battle. They at once tendered to Colonel Albright the command of the expedition; but he refused to accept it. They then importuned him to let a portion of his men, who were both anxious and willing, accompany them; but this, too, he refused.

Nothing daunted, however, the rangers and the volunteers arose by daybreak on Sunday morning, put their rifles in condition, eat their breakfast, and, with five days' provisions in their knapsacks, started for the mountain.

We sincerely regret that the most strenuous effort on our part to procure a list of this scout proved futile. Here and there we picked up the names of a few who were in it; but nothing would have given us greater pleasure than to insert a full and correct list of these brave men. In addition to the officers named, we may mention the following privates:—James Somerville, the two Colemans, two Hollidays, two brothers named Jones, a man named Grey, one of the Beattys, Michael Wallack, and Edward Milligan.

The path led close along the river, and the men marched in Indian file, as the path was narrow. When they reached the flat above where Temperance Mill now stands, and within thirty rods of the mouth of Sugar Run, the loud warwhoop rang upon the stillness of the Sabbath morning; a band of savages rose from the bushes on the left-hand side of the road, firing a volley at the same time, by which fifteen of the brave scout were stretched dead in the path. The remainder fled, in consternation, in every direction,—some over the river in the direction of Frankstown, others toward Fetter's Fort. A man named Jones, one of the fleetest runners, reached the fort first. To screen the scout from the odium of running, he reported the number of the enemy so large that Albright refused to let any of his command go to the relief of the unfortunate men.

As the Colemans were coming to the fort, they found the other Jones lying behind a log for the purpose of resting, as he said. Coleman advised him to push on to the fort, which he promised to do.

Captain Young at length started out with a party to bring in the wounded. The man Jones was found resting behind the log, but the rest was a lasting one; he was killed and scalped. Another man, who had been wounded, was also followed a short distance and killed and scalped,—making, in all, seventeen persons who fell by this sad and unlooked-for event. In addition to the seventeen killed, five were wounded, who were found concealed in various places in the woods and removed to the fort. Some reached the fort in safety, others were missing,—among the latter, Harry Woods, James Somerville, and Michael Wallack.

It appears that these three men started over the river, and ran up what is now known as O'Friel's Ridge, hotly pursued by a single savage. Woods and Wallack were in front, and Somerville behind, when the moccasin of the latter became untied. He stooped down to fix it, as it was impossible to ascend the steep hill with the loose moccasin retarding his progress. While in this position, the Indian, with uplifted tomahawk, was rapidly approaching him, when Woods turned suddenly and aimed with his empty rifle [5] at the Indian. This caused the savage to jump behind a tree scarcely large enough to cover his body, from which he peered, and recognised Woods.

"No hurt Woods!" yelled the Indian; "no hurt Woods!"

This Indian happened to be the son of the old Indian Hutson, to whom George Woods of Bedford paid a small annual stipend in tobacco, for delivering him from bondage. Hutson had frequently taken his son to Bedford, and it was by this means that he had become acquainted with Harry and readily recognised him. Woods, although he recognised Hutson, had been quite as close to Indians as he cared about getting; so the three continued their route over the ridge, and by a circuitous tramp reached the fort in the afternoon.

Many years afterward, long after the war, when Woods lived in Pittsburg, he went down to the Alleghany River to see several canoe-loads of Indians that had just arrived from above. He had scarcely reached the landing when one of the chiefs jumped out, shook him warmly by the hand, and said—

"Woods, you run like debble up Juniata Hill."

It was Hutson—by this time a distinguished chief in his tribe.

The fate of the unfortunate scout was soon known all over the country, expresses having been sent in every direction.

On Monday morning Captain Young again went out with a small party to bury the dead, and many of them were interred near the spot where they fell; while others, after the men got tired of digging graves, were merely covered with bark and leaves, and left on the spot to be food for the wolves, which some of the bodies unquestionably became, as Jones sought for that of his brother on Tuesday, and found nothing but the crushed remains of some bones.

In 1852, a young man in the employ of Mr. Burns exhumed one of these skeletons with the plough. It was found near the surface of the earth, on the bank of the river. The skull was perforated with a bullet-hole, and was in a remarkable state of preservation, although it had been in the ground uncoffined for a period of seventy-one years! It was placed in the earth again.

Immediately after the news of the massacre was spread, the people from Standing Stone and other places gathered at Fetter's; and on the Tuesday following a party of nearly one hundred men started in pursuit of the Indians. Colonel Albright was solicited to accompany this force with his command and march until they overtook the enemy; but he refused. The men went as far as Hart's Sleeping Place, but they might just as well have remained at home; for the savages, with the scalps of the scout dangling from their belts, were then far on their way to Detroit.

When the firing took place, it was plainly heard at the fort; and some of the men, fully convinced that the scout had been attacked, asked Colonel Albright to go out with his command to their relief. He merely answered by saying that he "knew his own business."

For his part in the matter, he gained the ill-will of the settlers, and it was very fortunate that his time expired when it did. The settlers were not much divided in opinion as to whether he was a rigid disciplinarian or a coward.

Men, arms, and ammunition, in abundance followed this last outrage; but it was the last formidable and warlike incursion into the Juniata Valley.

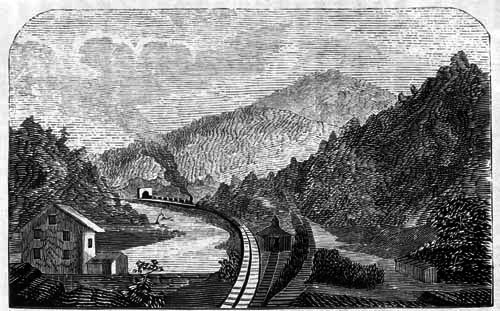

OLD BRIDGE NEAR PETERSBURG.

57 gruesome stories if Indian capture and torture