Depredations at the Mouth of Spruce Creek- The Indians Murder Levi Hicks and Scalp His Little Girl Who Miraculously Lived

We have already mentioned the Hicks family in a preceding chapter and incidentally mentioned their captivity for a number of years among the Indians. We have made the most unremitting exertions, yet we have failed to ascertain anything like a satisfactory account of this remarkable family. The name of Gersham Hicks figures in Miner's "History of Wyoming" as an Indian guide, while in the Archives he is noticed as an Indian interpreter, previous to the war of the Revolution. Where they were taken, or when released, is not positively known. One thing, however, is quite certain: that is, that they made themselves masters of both the habits and language of many of the Indians.

Mrs. Fee thinks they came to Water Street immediately after their release from captivity, and settled there. During their captivity they imbibed the Indian habit to such a degree that they wore the Indian costume, even to the colored eagle-feathers and little trinkets which savages seem to take so much delight in. Gersham and Moses were unmarried, but Levi, the elder, brought with him a half-breed as his wife, by whom he had a number of children. They all settled at Water Street, and commenced the occupation of farming. Subsequently, Levi rented from the Bebaults the tub-mill at or near the mouth of Spruce Creek.

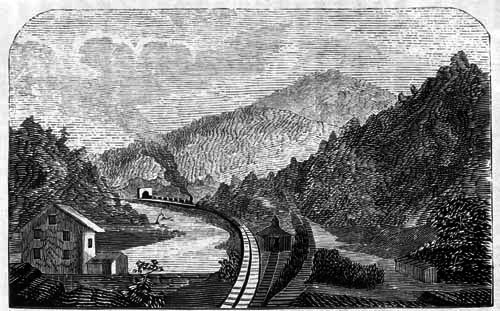

TUNNEL ON THE PENNSYLVANIA CENTRAL ROAD AT THE MOUTH OF SPRUCE CREEK.

When the Indian troubles commenced in the spring of 1778, he was repeatedly urged to go either to Lytle's or Lowry's Fort, and let the mill stand until the alarm had subsided. Hicks, however, obstinately refused, declaring that he was safe. It is thus apparent that he relied upon his intimate knowledge of the Indian character and language for safety, in case any of the marauders should find their way to what he looked upon as a sort of an out-of-the-way place,—a fatal case of misplaced confidence, notwithstanding it was asserted that the fall previous a party had attacked his cabin, and that, on his addressing them in their own language, they had desisted.

On the 12th of May, 1778, Hicks started his mill in the morning, as was his usual custom, and then repaired to breakfast. While in the house he procured a needle and thread, returned to the mill, replenished the hopper, and then seated himself near the door and commenced mending a moccasin. He had been occupied at this but a minute or two before he heard a rustling in the bushes some ten or fifteen yards in front of him. The idea of there being Indians in the vicinity never entered his head; nobody had seen or heard of any in the settlement. Consequently, in direct violation of an established custom, he walked forward to ascertain the cause of the commotion in the bushes, leaving his rifle leaning against the mill. He advanced but one or two steps before he was shot through the heart.

His wife, who was in the house at the time, hearing the report, ran to the door, and in an instant comprehended how matters stood. She opened the back door, ran down the river to a fording, crossed over, and, with all the speed she could command, hastened over the mountain to Lytle's Fort. Near Alexandria she met a man on horseback, who, noticing her distracted condition, demanded what the matter was. She explained as best she could, when the man turned back and rode rapidly toward the fort to apprise the people of what had occurred. It was then that the woman fairly recovered her senses, and, on looking around for the first time, she noticed her little son, about ten years old, who had followed her. The sight of him reminded her of her family of children at home, at the mercy of the savages, and all the mother's devotion was aroused within her. She picked up her boy, and, exhausted as she was, hastened toward the fort with him.

As it subsequently appeared, one of the children of Mrs. Hicks,—a girl between three and four years of age,—directly after her escape, went out to see her father, just while the savages were in the act of scalping him. She was too young to comprehend the act clearly, but, seeing the blood about his head, she commenced crying, and screamed, "My pappy! my pappy! what are you doing to my poor pappy?"

One of the Indians drew his tomahawk from his belt and knocked the child down, after which he scalped it; and, without venturing to the house, the savages departed. Mrs. Hicks reached the fort, and the news of the murder soon spread over the country, but the usual delays occurred in getting up a scout to follow the marauders. Some declared their unwillingness to go unless there was a large force, as the depredators might only be some stragglers belonging to a large party; others, that their rifles were out of order; and others again pleaded sickness. In this way the day slipped around, and in the mean time the savages got far beyond their reach, even in case the scout could have been induced to follow them.

Next morning, however, a party mustered courage and went over to the mill, where they found Hicks scalped on the spot where he fell, and his rifle gone.

The inside of the house presented one of the saddest spectacles ever witnessed in the annals of savage atrocities. Two of the children were lying upon the floor crying, and the infant in the cradle, for the want of nourishment had apparently cried until its crying had subsided into the most pitiful moanings; while the little girl that had been scalped sat crouched in a corner, gibbering like an idiot, her face and head covered with dry clotted blood!

Of course, considering the start the Indians had, it was deemed useless to follow them; so they buried Hicks near the mill, and removed the family to the fort.

It may seem a little singular, nevertheless it is true, that the child, in spite of its fractured skull and the loss of its scalp, actually recovered, and lived for a number of years after the outrage, although its wounds were never dressed by a physician. It was feeble-minded, however, owing to the fracture.

As no other family resided near the mill, no person could be induced to take it after Hicks was murdered, and it stood idle for years.

The murder of Hicks created the usual amount of alarm, but no depredations followed in the immediate neighborhood for some time after his death.

57 horrid stories of captured and tortured