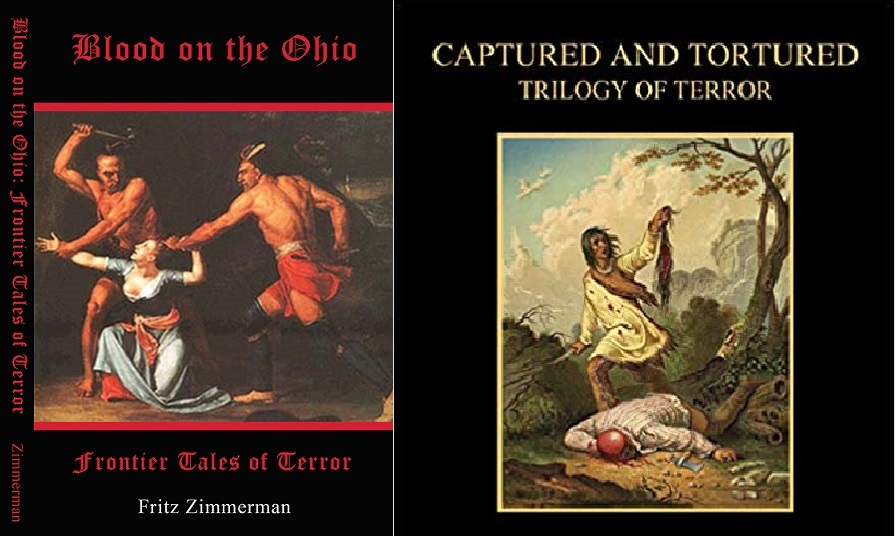

Being Captured by Native Americans

It was their custom to carry off the women and children. If the children were hindered the march of their mothers, or if they cried and endangered or annoyed their captors, they were tomahawked, or their brains were dashed out against the trees. But if they were well grown, and strong enough to keep up with the rest, they were hurried sometimes hundreds of miles into the wilderness. There the fate of all prisoners was decided in solemn council of the tribe. If any men had been taken, especially such as had made a hard fight for their freedom and had given proof of their courage, they were commonly tortured to death by fire in celebration of the victory won over them; though it sometimes happened that young men who had caught the fancy or affection of the Indians were adopted by the fathers of sons lately lost in battle. The older women became the slaves and drudges of the squaws and the boys and girls were parted from their mothers and scattered among the savage families. The boys grew up hunters and trappers, like the Indian boys, and the girls grew up like the Indian girls, and did the hard work which the warriors always left to the women. The captives became as fond of their wild, free life as the savages themselves, and they found wives and husbands among the youths and maidens of their tribe. If they were given up to their own people, as might happen in the brief intervals of peace, they pined for the wilderness, which called to their homesick hearts, and sometimes they stole back to it. They seem rarely to have been held for ransom, as the captives of the Indians of the Western plains were in our time. It was a tie of real love that bound them and their savage friends together, and it was sometimes stronger than the tie of blood. But this made their fate all the crueler to their kindred; for whether they lived or whether they died, they were lost to the fathers and mothers, and brothers and sisters whom they had been torn from; and it was little consolation to these that they had found human mercy and tenderness in the breasts of savages who in all else were like ravening beasts. It was rather an agony added to what they had already suffered to know that somewhere in the trackless forests to the westward there was growing up a child who must forget them. The time came when something must be done to end all this and to put a stop to the Indian attacks on the frontiers of Pennsylvania and Virginia. The jealous colonies united with the jealous mother country, and a little army of British regulars and American recruits was sent into Ohio under the lead of Colonel Henry Bouquet to force the savages to give up their captives.