Man Boiled Alive and the Retribution

Among all the early pioneers of the upper end of the Juniata Valley none was better known to the Indians than Thomas Coleman. His very name inspired them with terror; and, in all their marauding, they carefully avoided his neighborhood. He was, emphatically, an Indian-hater,—the great aim and object of whose life appeared to be centred in the destruction of Indians. For this he had a reason—a deep-seated revenge to gratify, a thirst that all the savage blood in the land could not slake,—superinduced by one of the most cruel acts of savage atrocity on record.

It appears that the Coleman family lived on the West Branch of the Susquehanna at an early day. Their habitation, it would also appear, was remote from the settlements; and their principal occupation was hunting and trapping in winter, boiling sugar in spring, and tilling some ground they held during the summer. Where they originally came from was rather a mystery; but they were evidently tolerably well educated, and had seen more refined life than the forest afforded. Nevertheless, they led an apparently happy life in the woods. There were three brothers of them, and, what is not very common nowadays, they were passionately attached to each other.

Early in the spring,—probably in the year 1763,—while employed in boiling sugar, one of the brothers discovered the tracks of a bear, when it was resolved that the elder two should follow and the younger remain to attend to the sugar-boiling. The brothers followed the tracks of the bear for several hours, but, not overtaking him, agreed to return to the sugar-camp. On their arrival, they found the remains of their brother boiled to a jelly in the large iron kettle! A sad and sickening sight, truly; but the authors of the black-hearted crime had left their sign-manual behind them,—an old tomahawk, red with the gore of their victim, sunk into one of the props which supported the kettle. They buried the remains as best they could, repaired to their home, broke up their camp, abandoned their place a short time after, and moved to the Juniata Valley.

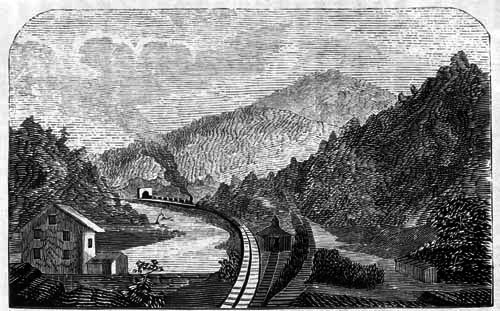

Their first location was near the mouth of the river; but gradually they worked their way west, until they settled somewhere in the neighborhood of the mouth of Spruce Creek, on the Little Juniata, about the year 1770. A few years after, the two brothers, Thomas and Michael, the survivors of the family, moved to the base of the mountain, in what now constitutes Logan township, near where Altoona stands, which then was included within the Frankstown district.

These men were fearless almost to a fault; and on the commencement of hostilities, or after the first predatory incursion of the savages, it appears that Thomas gave himself up solely to hunting Indians. He was in all scouting parties that were projected, and always leading the van when danger threatened; and it has very aptly, and no doubt truly, been said of Coleman, that when no parties were willing to venture out he shouldered his rifle and ranged the woods alone in hopes of occasionally picking up a stray savage or two. That his trusty rifle sent many a savage to eternity there is not a shadow of doubt. He, however, never said so. He was never known to acknowledge to any of his most intimate acquaintances that he had ever killed an Indian; and yet, strange as it may seem, he came to the fort on several occasions with rather ugly wounds upon his body, and his knife and tomahawk looked as if they had been used to some purpose. Occasionally, too, a dead savage was found in his tracks, but no one could tell who killed him. For such reserve Mr. Coleman probably had his own motives; but that his fights with the savages were many and bloody is susceptible of proof even at this late day. We may incidentally mention that both the Colemans accompanied Captain Blair's expedition to overtake the tories, and Thomas was one of the unfortunate "Bedford Scout."

To show how well Thomas was known, and to demonstrate clearly that he had on sundry occasions had dealings with some of the savages without the knowledge of his friends, we may state that during the late war with Great Britain, on the Canadian frontier, a great many Indians made inquiries about "Old Coley;" and especially one, who represented himself as being a son of Shingas, pointed out to some of Captain Allison's men, who were from Huntingdon county, a severe gash on his forehead, by which he said he should be likely to remember "Coley" for the balance of his life.

In the fall of 1777, Fetter's Fort was occupied by some twenty-five men capable of bearing arms, belonging to the Frankstown district. Among these were both the Colemans, their own and a number of other settler's families.

The Indians who had murdered the Dunkards, it appears, met about a mile east of Kittaning Point, where they encamped, (the horses and plunder having probably been sent on across the mountain,) in order to await the arrival of the scattered forces. Thomas and Michael Coleman and Michael Wallack had left Fetter's Fort in the morning for the purpose of hunting deer. During the day, snow fell to the depth of some three or four inches; and in coming down the Gap, Coleman and his party crossed the Indian trail, and discovered the moccasin tracks, which they soon ascertained to be fresh. It was soon determined to follow them, ascertain their force, and then repair to the fort and give the alarm. They had followed the trail scarcely half a mile before they saw the blaze of the fire and the dusky outlines of the savages seated around it. Their number, of course, could not be made out, but they conjectured that there must be in the neighborhood of thirty; but, in order to get a crack at them, Thomas Coleman made his companions promise not to reveal their actual strength to the men in the fort. Accordingly they returned and made report—once, for a wonder, not exaggerated, but rather underrated. The available force, amounting to sixteen men, consisting of the three above named, Edward Milligan, Samuel Jack, William Moore, George Fetter, John Fetter, William Holliday, Richard Clausin, John McDonald, and others whose names are not recollected, loaded their rifles and started in pursuit of the savages. By the time they reached the encampment, it had grown quite cold, and the night was considerably advanced; still some ten or twelve Indians were seated around the fire. Cautiously the men approached, and with such silence that the very word of command was given in a whisper. When within sixty yards, a halt was called. One Indian appeared to be engaged in mixing paint in a pot over the fire, while the remainder were talking,—probably relating to each other the incidents attending their late foray. Their rifles were all leaning against a large tree, and Thomas Coleman conceived the bold design of approaching the tree, although it stood but ten feet from the fire, and securing their arms before attacking them. The achievement would have been a brilliant one, but the undertaking was deemed so hazardous that not a man would agree to second him in so reckless and daring an enterprise. It was then agreed that they all should aim, and at the given word fire. Coleman suggested that each man should single out a particular savage to fire at; but his suggestion was lost upon men who were getting nervous by beginning to think their situation somewhat critical. Aim—we will not call it deliberate—was taken, the word "fire!" was given, and the sharp report of the rifles made the dim old woods echo. Some three or four of the savages fell, and those who were sitting around the fire, as well as those who were lying upon the ground, instantly sprang to their feet and ran to the tree where their rifles stood. In the mean time, Coleman said—

"Quick! quick! boys, load again! we can give them another fire before they know where we are!"

But, on looking around, he was surprised to find nobody but Wallack and Holliday left to obey his order! The number proving unexpectedly large, the majority became frightened, and ran for the fort.

The Indians, in doubt as to the number of their assailants, took an early opportunity to get out of the light caused by the fire and concealed themselves behind trees, to await the further operations of this sudden and unexpected foe.

Coleman, Wallack, and Holliday, deeming themselves too few in number to cope with the Indians, followed their friends to Fetter's Fort.

Early the next morning, all the available force of the fort started in pursuit of the Indians. Of course, they did not expect to find them at the encampment of the night previous; so they took provisions and ammunition along for several days' scout, in order, if possible, to overtake the savages before they reached their own country. To this end, Coleman was appointed to the command, and the march was among those denominated by military men as forced.

When they reached the scene of the previous night's work, the evidence was plain that the savages had departed in the night. This the hunters detected by signs not to be mistaken by woodsmen; there was not a particle of fire left, and the coals retained no warmth. The tracks of the savages west of the fire, too, showed that they conformed to those east of the fire, in appearance, whereas, those made by the hunters in the morning looked quite differently. It was then evident that the Indians had a start of some six or eight hours.

On the spot where the fire had been the small earthen paint-pot was found, and in it a portion of mixed paint. Near the fire, numerous articles were picked up:—several scalping-knives, one of which the owner was evidently in the act of sharpening when the volley was fired, as the whetstone was lying by its side; several tomahawks, a powder-horn, and a number of other trifling articles. The ground was dyed with blood, leaving no doubt remaining in regard to their execution the night previous. They had both killed and wounded,—but what number was to remain to them forever a mystery, for they carried both dead and wounded with them.

This was a singular trait in savage character. They never left the body of a dead or wounded warrior behind them, if by any possible human agency it could be taken with them. If impossible to move it far, they usually buried it, and concealed the place of burial with leaves; if in an enemy's country, they removed the remains, even if in a state of partial decay, on the first opportunity that offered. To prevent the dead body of a brave from falling into the hands of an enemy appeared with them a religious duty paramount even to sepulture. As an evidence of this, Sam Brady, the celebrated Indian-fighter, once waylaid and shot an old Indian on the Susquehanna who was accompanied by his two sons, aged respectively sixteen and eighteen years. The young Indians ran when their father fell, and Brady left the body and returned home. Next morning, having occasion to pass the place, he found the body gone, and by the tracks he ascertained that it had been removed by the lads. He followed them forty miles before he overtook them, bearing their heavy burden with the will of sturdy work-horses. Brady had set out with the determination of killing both, but the sight so affected him that he left them to pursue their way unharmed; and he subsequently learned that they had carried the dead body one hundred and sixty miles. Brady said that was the only chance in his life to kill an Indian which he did not improve. It may be that filial affection prompted the young savages to carry home the remains of their parents; nevertheless, it is known that the dead bodies of Indians—ordinary fighting-men—were carried, without the aid of horses, from the Juniata Valley to the Indian burial-ground at Kittaning, and that too in the same time it occupied in making their rapid marches between the two points.

But to return to our party. After surveying the ground a few moments, they followed the Indian trail—no difficult matter, seeing that it was filled with blood—until they reached the summit of the mountain, some six or eight miles from the mouth of the Gap. Here a consultation was held, and a majority decided that there was no use in following them farther. Coleman, however, was eager to continue the chase, and declared his willingness to follow them to their stronghold, Kittaning.

This issue, successful though it was, did not fail to spread alarm through the sparsely-settled country. People from the neighborhood speedily gathered their families into the fort, under the firm impression that they were to be harassed by savage warfare not only during the winter, but as long as the Revolutionary struggle was to continue. However, no more Indians appeared; this little cloud of war was soon dispelled, and the people betook themselves to their homes before the holidays of 1777, where they remained during the winter without molestation.

It is said of old Tommy Coleman—but with what degree of truth we are unable to say—that, about twenty years ago, hearing of a delegation of Indians on their way to Washington, he shouldered his trusty old rifle, and went to Hollidaysburg. There, hearing that they had gone east on the canal packet, he followed them some three miles down the towing-path, for the express purpose of having a crack at one of them. This story—which obtained currency at the time, and is believed by many to this day—was probably put into circulation by some one who knew his inveterate hatred of Indians. An acquaintance of his informs us that he had business in town on the day on which the Indians passed through; hence his appearance there. His gun he always carried with him, even on a visit to a near neighbor. That he inquired about the Indians is true; but it was merely out of an anxiety to see whether they looked as they did in days of yore. His business led him to Frankstown, but that business was not to shoot Indians; for, if he still cherished any hatred toward the race, he had better sense than to show it on such an occasion.

He died at his residence, of old age, about fifteen years ago, beloved and respected by all. Peace to his ashes!