Massacre of the Holiday Family Children

William and Adam Holliday, cousins, emigrated from the North of Ireland about 1750, and settled in the neighborhood of the Manor, in Lancaster county. The feuds which existed between the Irish and German emigrants, as well as the unceasing efforts of the proprietary agents to keep emigrants from settling upon their lands, induced the Hollidays to seek a location farther west. Conococheague suggested itself to them as a suitable place, because it was so far removed from Philadelphia that the proprietors could not well dispossess them; and, the line never having been established, it was altogether uncertain whether the settlement was in Pennsylvania or Maryland. Besides, it possessed the advantage of being tolerably well populated. Accordingly, they settled on the banks of the Conococheague, and commenced clearing land, which they purchased and paid for soon after the survey. During both the French and Indian wars of 1755-56 and the war of 1762-63 the Hollidays were in active service. At the destruction of Kittaning, William Holliday was a lieutenant in Colonel Armstrong's company, and fought with great bravery in that conflict with the savages. The Hollidays were emphatically frontier-men; and on the restoration of peace in 1768, probably under the impression that the Conococheague Valley was becoming too thickly populated, they disposed of their land, placed their families and effects upon pack-horses, and again turned their faces toward the west. They passed through Aughwick, but found no unappropriated lands there worthy of their attention. From thence they proceeded to the Standing Stone, but nothing offered there; nor even at Frankstown could they find any inducement to stop; so they concluded to cross the mountain by the Kittaning Path and settle on the Alleghany at or near Kittaning. William knew the road, and had noticed fine lands in that direction.

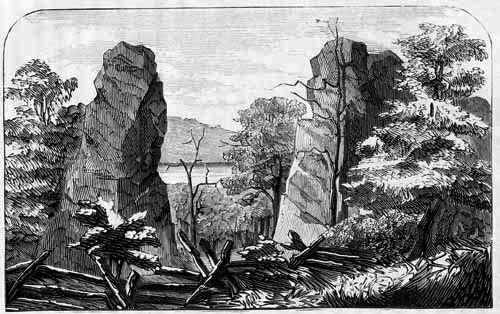

CHIMNEY ROCKS OPPOSITE HOLLIDAYSBURG.

However, when they reached the place where Hollidaysburg now stands, and were just on the point of descending the hill toward the river, Adam halted, and declared his intention to pitch his tent and travel no farther. He argued with his cousin that the Indian titles west of the mountains were not extinguished; and if they bought from the Indians, they would be forced, on the extinguishment of their titles, to purchase a second time, or lose their lands and live in constant dread of the savages. Although William had a covetous eye on the fine lands of the Alleghany, the wise counsel of Adam prevailed, and they dismounted and prepared to build a temporary shelter. When Adam drove the first stake into the ground he casually remarked to William, "Whoever is alive a hundred years after this will see a tolerable-sized town here, and this will be near about the middle of it." This prediction has been verified to the letter long before the expiration of the allotted time.

In a day or two after a shelter had been erected for the families, William crossed the river to where Gaysport now stands, for the purpose of locating. The land, however, was too swampy, and he returned. The next day he crossed again, and found a ravine, south of where he had been prospecting, which appeared to possess the desired qualifications; and there he staked out a farm,—the one now owned by Mr. J. R. Crawford. Through this farm the old Frankstown and Johnstown Road ran for many years,—the third road constructed in Pennsylvania crossing the Alleghany Mountains.

These lands belonged to the new purchase, and were in the market at a very low price, in order to encourage settlers on the frontier. Accordingly, Adam Holliday took out a warrant for 1000 acres, comprising all the land upon which Hollidaysburg now stands. The lower or southern part was too marshy to work; so Mr. Holliday erected his cabin near where the American House now stands, and made a clearing on the high ground stretching toward the east.

In the mean time, William Holliday purchased of Mr. Peters 1000 acres of land, which embraced the present Crawford and Jackson farms and a greater part of Gaysport. Some years after, finding that he had more land than he could conveniently cultivate, he disposed of nearly one-half of his original purchase to his son-in-law, James Somerville.

Adam Holliday, too, having a large lot of land, disposed of a portion of it to Lazarus Lowry. Thus matters progressed smoothly for a time, until, unfortunately, a Scotchman, named Henry Gordon, in search of lands, happened to see and admire his farm. Gordon was a keen, shrewd fellow, and in looking over the records of the land-office he discovered a flaw or informality in Adam's grant. He immediately took advantage of his discovery and took out a patent for the land. Litigation followed, as a matter of course. Gordon possessed considerable legal acumen, and had withal money and a determined spirit. The case was tried in the courts below and the courts above,—decided sometimes in favor of one party and sometimes in favor of the other, but eventually resulted in Gordon wresting from Adam Holliday and Lazarus Lowry all their land. This unfortunate circumstance deeply afflicted Mr. Holliday, for he had undoubtedly been grossly wronged by the adroitness and cunning of Gordon; but relief came to him when he least expected it. When the war broke out, Gordon was among the very first to sail for Europe; and soon after the Council proclaimed him an attainted traitor, and his property was confiscated and brought under the hammer. The circumstances under which he had wrested the property from Holliday were known, so that no person would bid, which enabled him to regain his land at a mere nominal price. He then went on and improved, and built a house on the bank of the river, near where the bridge connects the boroughs of Hollidaysburg and Gaysport. The very locust-trees that he planted seventy-eight years ago, in front of his door, are still standing.

During the alarms and troubles which followed in the course of the war, Adam Holliday took a conspicuous part in defending the frontier. He aided, first, in erecting Fetter's Fort, and afterward expended his means in turning Titus's stable into a fort. This fort was located on the flat, nearly opposite the second lock below Hollidaysburg, and the two served as a place of refuge for all the settlers of what was then merely called the Upper End of Frankstown District. He also, with his own money, purchased provisions, and through his exertions arms and ammunition were brought from the eastern counties. His courage and energy inspired the settlers to make a stand at a time when they were on the very point of flying to Cumberland county. In December, 1777, Mr. Holliday visited Philadelphia for the purpose of securing a part of the funds appropriated to the defence of the frontier. The following letter to President Wharton was given to him by Colonel John Piper, of Bedford county:—

Bedford County, December 19, 1777.

Sir:—Permit me, sir, to recommend to you, for counsel and direction, the bearer, Mr. Holliday, an inhabitant of Frankstown, one of the frontier settlements of our county, who has, at his own risk, been extremely active in assembling the people of that settlement together and in purchasing provisions to serve the militia who came to their assistance. As there was no person appointed either to purchase provisions or to serve them out, necessity obliged the bearer, with the assistance of some neighbors, to purchase a considerable quantity of provisions for that purpose, by which the inhabitants have been enabled to make a stand. His request is that he may be supplied with cash not only to discharge the debts already contracted, but likewise to enable him to lay up a store for future demand. I beg leave, sir, to refer to the bearer for further information, in hopes you will provide for their further support. Their situation requires immediate assistance.

I am, sir, with all due respect, your Excellency's most obedient humble servant,

John Piper.

Mr. Holliday's mission was successful; and he returned with means to recruit the fort with provisions and ammunition, and continued to be an active and energetic frontier-man during all the Indian troubles which followed.

Notwithstanding the distracted state of society during the Revolution, William Holliday devoted much time and attention to his farm. His family, consisting of his wife, his sons John, William, Patrick, Adam, and a lunatic whose name is not recollected, and his daughter Janet, were forted at Holliday's Fort; and it was only when absolute necessity demanded it that they ventured to the farm to attend to the crops, after the savage marauders so boldly entered the settlements.

James, who we believe was next to the eldest of William Holliday's children, joined the Continental army soon after the war broke out. He is represented as having been a noble-looking fellow, filled with enthusiasm, who sought for, and obtained without much difficulty, a lieutenant's commission. He was engaged in several battles, and conducted himself in such a manner as to merit the approbation of his senior officers; but he fell gloriously at Brandywine, while the battle was raging, pierced through the heart by a musket-ball. He was shot by a Hessian, who was under cover, and who had, from the same place, already dispatched a number of persons. But this was his last shot; for a young Virginian, who stood by the side of Holliday when he fell, rushed upon the Hessian, braving all danger, and hewed him to pieces with his sword before any defence could be made.

The death of young Holliday was deeply lamented by his companions-in-arms, for he was brave and generous, and had not a single enemy in the line. His friends, after the battle, buried him near the spot where he fell; and it is doubtful whether even now a hillock of greensward is raised to his memory.

About the beginning of the year 1779, the Indians along the frontier, emboldened by numerous successful depredations, came into Bedford county—within the boundaries of which Holliday's Fort then was—in such formidable bands that many of the inhabitants fled to the eastern counties. The Hollidays, however, and some few others, tarried, in the hope that the Executive Council would render them aid. The following petition, signed by William Holliday and others, will give the reader some idea of the distress suffered by the pioneers; it was drawn up on the 29th of May, 1779:—

To the Honorable President and Council:—

The Indians being now in the county, the frontier inhabitants being generally fled, leaves the few that remains in such a distressed condition that pen can hardly describe, nor your honors can only have a faint idea of; nor can it be conceived properly by any but such as are the subjects thereof; but, while we suffer in the part of the county that is most frontier, the inhabitants of the interior part of this county live at ease and safety.

And we humbly conceive that by some immediate instruction from Council, to call them that are less exposed to our relief, we shall be able, under God, to repulse our enemies, and put it in the power of the distressed inhabitants to reap the fruits of their industry. Therefore, we humbly pray you would grant us such relief in the premises as you in your wisdom see meet. And your petitioners shall pray, etc.

N.B.—There is a quantity of lead at the mines (Sinking Valley) in this county Council may procure for the use of said county, which will save carriage, and supply our wants with that article, which we cannot exist without at this place; and our flints are altogether expended. Therefore, we beg Council would furnish us with those necessaries as they in their wisdom see cause.

P.S.—Please to supply us with powder to answer lead.

(Signed)

William Holliday, P.M.

Thomas Coulter, Sheriff.

Richard J. Delapt, Captain.

Sam. Davidson.

The prayer of these petitioners was not speedily answered, and Holliday's Fort was evacuated soon after. The Council undoubtedly did all in its power to give the frontiers support; but the tardy movements of the militia gave the savages confidence, and drove the few settlers that remained almost to despair. Eventually relief came, but not sufficient to prevent Indian depredations. At length, when these depredations and the delays of the Council in furnishing sufficient force to repel these savage invasions had brought matters to such a crisis that forbearance ceased to be a virtue, the people of the neighborhood moved their families to Fort Roberdeau, in Sinking Valley, and Fetter's Fort, and formed themselves into scouting parties, and by these means protected the frontier and enabled the settlers to gather in their crops in 1780; still, notwithstanding their vigilance, small bands of scalp-hunters occasionally invaded the county, and, when no scalps were to be found, compromised by stealing horses, or by laying waste whatever fell in their way.

In 1781, when Continental money was so terribly depreciated that it took, in the language of one of the old settlers, "seventeen dollars of it to buy a quart of whiskey," government was in too straitened a condition to furnish this frontier guard with ammunition and provisions, so that the force was considerably reduced. Small scouting parties were still kept up, however, to watch the savages, who again made their appearance in the neighborhood in the summer, retarding the harvest operations.

About the middle of July, the scouts reported every thing quiet and no traces of Indians in the county. Accordingly, Mr. Holliday proceeded to his farm, and, with the aid of his sons, succeeded in getting off and housing his grain. Early in August, Mr. Holliday, accompanied by his sons Patrick and Adam and his daughter Janet, then about fourteen years of age, left Fort Roberdeau for the purpose of taking off a second crop of hay. On their arrival at the farm they went leisurely to work, and mowed the grass. The weather being extremely fine, in a few days they began to haul it in on a rudely-constructed sled, for in those primitive days few wagons were in use along the frontiers. They had taken in one load, returned, and filled the sled again, when an acquaintance named McDonald, a Scotchman, came along on horseback. He stopped, and they commenced a conversation on the war. William Holliday was seated upon one of the horses that were hitched to the sled, his two sons were on one side of him, and his daughter on the opposite side. All of the men, as was customary then, were armed with rifles. While this conversation was going on, and without the slightest previous intimation, a volley was suddenly fired from a thicket some sixty or seventy yards off, by which Patrick and Adam were instantly killed and the horse shot from under Mr. Holliday. The attack was so sudden and unexpected that a flash of lightning and a peal of thunder from a cloudless sky could not have astonished him more. The echoes of the Indian rifles had scarcely died away before the Indians themselves, to the number of eight or ten, with a loud "whoop!" jumped from their place of concealment, some brandishing their knives and hatchets and others reloading their rifles.

Appalled at the shocking tragedy, and undecided for a moment what course to pursue, Holliday was surprised to see McDonald leap from his horse, throw away his rifle, run toward the Indians, and, with outstretched arms, cry "Brother! Brother!" which it appears was a cry for quarter which the savages respected. Holliday, however, knew too much of the savage character to trust to their mercy—more especially as rebel scalps commanded nearly as good a price in British gold in Canada as prisoners; so on the impulse of the moment he sprang upon McDonald's horse and made an effort to get his daughter up behind him. But he was too late. The Indians were upon him, and he turned into the path which led down the ravine. The yells of the savages frightened the horse, and he galloped down the path; but even the clattering of his hoofs did not drown the dying shrieks of his daughter, who was most barbarously butchered with a hatchet.

In a state of mind bordering on distraction, Holliday wandered about until nearly dark, when he got upon the Brush Mountain trail, on his way to Sinking Valley. His mind, however, was so deeply affected that he seemed to care little whither he went; and, the night being exceedingly dark, the horse lost the trail and wandered about the mountain for hours. Just at daybreak Mr. Holliday reached the fort, haggard and careworn, without hat or shoes, his clothes in tatters and his body lacerated and bleeding. He did not recognise either the fort or the sentinel on duty. He was taken in, and the fort alarmed, but it was some time before he could make any thing like an intelligible statement of what had occurred the day previous. Without waiting for the particulars in detail, a command of fifteen men was despatched to Holliday's farm. They found the bodies of Patrick and Adam precisely where they fell, and that of Janet but a short distance from the sled, and all scalped. As soon as the necessary arrangements could be made, the bodies of the slain were interred on the farm; and a rude tombstone still marks the spot where the victims of savage cruelty repose.

This was a sad blow to Mr. Holliday; and it was long before he recovered from it effectually. But the times steeled men to bear misfortunes that would now crush and annihilate the bravest.

The Scotchman McDonald, whom we have mentioned as being present at the Holliday massacre, accompanied the savages, as he afterward stated, to the Miami Valley, where he adopted their manners and customs, and remained with them until the restoration of peace enabled him to escape. He returned to the Valley of the Juniata; but he soon found that Holliday had prejudiced the public mind against him by declaring the part he took at the time of the massacre to have been cowardly in the extreme, notwithstanding that the cowardice of McDonald actually saved Holliday's life, by affording him means to escape. The people generally shunned McDonald, and he led rather an unenviable life; yet we might suppose, taking all the circumstances into consideration, that, in illustrating the axiom that "self-preservation is the first law of nature," he did nothing more than any man, with even less prudence than a canny Scotchman, would have done. But any thing having the least squinting toward cowardice was deemed a deadly sin by the pioneers, and McDonald soon found it necessary to seek a home somewhere else.

After the declaration of peace, or, rather, after the ratification of the treaty, Gordon came back to Pennsylvania and claimed his land under its stipulation. He had no difficulty in proving that he had never taken up arms against the colonies, and Congress agreed to purchase back his lands.

The Commissioners to adjust claims, after examining the lands, reported them worth sixteen dollars an acre; and this amount was paid to Adam Holliday, who suddenly found himself the greatest monied man in this county—having in his possession sixteen or seventeen thousand dollars.

Adam Holliday lived to a good old age, and died at his residence on the bank of the river, in 1801. He left two heirs—his son John, and a daughter married to William Reynolds.

After the estate was settled up, it was found that John Holliday was the richest man in this county. He married the daughter of Lazarus Lowry, of Frankstown, in 1803, and in 1807 he left for Johnstown, where he purchased the farm, and all the land upon which Johnstown now stands, from a Dr. Anderson, of Bedford. Fearing the place would never be one of any importance, John Holliday, in a few years, sold out to Peter Livergood for eight dollars an acre, returned to Hollidaysburg, and entered into mercantile pursuits.

William Holliday, too, died at a good old age, and lies buried on his farm by the side of his children, who were massacred by the Indians.

In the ordinary transmutation of worldly affairs, the lands of both the old pioneers passed out of the hands of their descendants; yet a beautiful town stands as a lasting monument to the name, and the descendants have multiplied until the name of Holliday is known not only in Pennsylvania, but over the whole Union.

[Note.—There are several contradictory accounts in existence touching the massacre of the Holliday children. Our account of it is evidently the true version, for it was given to us by Mr. Maguire, who received it from Mr. Holliday shortly after the occurrence of the tragedy.

It may be as well here to state that the original Hollidays were Irish-men and Presbyterians. It is necessary to state this, because we have heard arguments about their religious faith. Some avow that they were Catholics, and as an evidence refer to the fact that William called one of his offspring "Patrick." Without being able to account for the name of a saint so prominent in the calendar as Patrick being found in a Presbyterian family, we can only give the words of Mr. Maguire, who said:—

"I was a Catholic, and old Billy and Adam Holliday were Presbyterians; but in those days we found matters of more importance to attend to than quarrelling about religion. We all worshipped the same God, and some of the forms and ceremonies attending church were very much alike, especially in 1778, when the men of all denominations, in place of hymn-books, prayer-books, and Bibles, carried to church with them loaded rifles!"

It may be as well to state here also that the McDonald mentioned had two brothers—one a daring frontier-man, the other in the army,—so that the reader will please not confound them.]

57 gruesome stories in Indian torture and capture