Revolutionary War Tory Accompanied by Indians Kill One Settler and Kidnaps a Woman and Her Children

During the troubles which followed immediately after the declaration of war, a great many depredations were committed by the tories, that were invariably charged to the Indians. As we have stated in the preceding chapter, the patriots and the tories, in point of numbers, were about equally divided in many of the settlements of what now constitutes Huntingdon county; yet the victims of tory wrongs could not for a long time bring themselves to believe that they were inflicted by their neighbors. Barns and their valuable contents were laid in ashes, cattle were shot or poisoned, and all charged to the Indians, although scouts were constantly out, but seldom, if ever, got upon their trail.

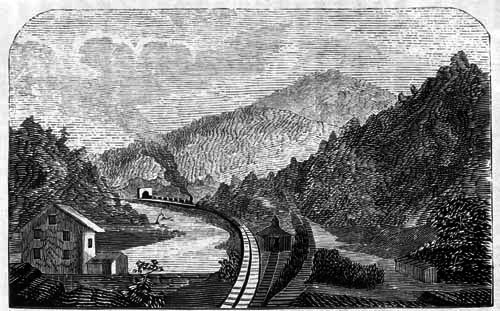

In a small isolated valley, about a mile south of Jack's Narrows, lived a notorious tory named Jacob Hare. We could not ascertain what countryman Hare was, nor any thing of his previous history. He owned a large tract of land, which he was exceedingly fearful of losing. Hence he remained loyal to the king, under the most solemn conviction, no doubt, that the struggle would terminate in favor of the crown. He is represented as having been a man of little intelligence, brutal and savage, and cowardly in the extreme. Although he did not take up arms positively against the Colonists, he certainly contributed largely to aid the British in crushing them.

A short time previous to the Weston Tory Expedition, a young man named Loudenslager, who resided in the upper end of Kishicoquillas, left his home on horseback, to go to Huntingdon, where Major Cluggage was enlisting men to guard the lead mines of Sinking Valley. It was young Loudenslager's intention to see how things looked, and, if they suited, he would join Cluggage's command and send his horse home. As he was riding leisurely along near the head of the valley, some five or six Indians, accompanied by a white man, appeared upon an eminence, and three of them, including the white man, fired at him. Three buckshot and a slug lodged in his thigh, and one bullet whistled past his ear, while one of the buckshot struck the horse. The animal took fright, and started off at a full gallop. Loudenslager, although his thigh-bone was shattered and his wound bled so profusely that he left a trail of blood in his wake, heroically clung to his horse until he carried him to the Standing Stone fort.

Weak and faint from the loss of blood, when he got there he was unable to move, and some of the people carried him in and cared for him as well as they could; but he was too much exhausted to give any account of the occurrence. After some restoratives were applied, he rallied, and gave a statement of the affair. His description of the white man in company with the Indians was so accurate, that the people knew at once that Hare, if not the direct author, was the instigator, of this diabolical outrage.

Loudenslager, for want of good medical attendance or an experienced surgeon, grew worse, and the commander, to alleviate his sufferings if possible, placed him in a canoe, and despatched him, accompanied by some men, on his way to Middletown,—then the nearest point of any importance; but he died after the canoe had descended the river but a few miles.

The excitement occasioned by the shooting of young Loudenslager was just at its height when more bad news was brought to Standing Stone Fort.

On the same day, the same party that shot Loudenslager went to the house of Mr. Eaton, (though probably unaccompanied by Hare,) in the upper end of the same valley; but, not finding any men about the house,—Mr. Eaton being absent,—they took captives Mrs. Eaton and her two children, and then set fire to all the buildings. The work of devastation was on the point of being completed when Mr. Eaton reached his home. He did not wait to see his house entirely reduced to ashes, but rode to Standing Stone as fast as his horse could carry him, and spread the alarm. The exasperated people could hardly muster sufficient patience to hear the particulars before they started in pursuit of the enemy. They travelled with all the speed that energetic and determined men could command, scouring the country in every direction for a period of nearly a week, but heard no tidings of Mrs. Eaton and her children, and were forced to give her up as lost.

This aroused the wrath of the settlers, and many of them were for dealing out summary punishment to Hare as the instigator; but, in the absence of proof, he was not even brought to trial for the Loudenslager murder, of which he was clearly guilty. The act, however, put people upon their guard; the most notorious known tory in the county had openly shown his hand, and they knew what to expect of him.

Mr. Eaton—broken-hearted, and almost distracted—hunted for years for his wife and children; and, as no tidings could be had of them, he was at last reluctantly forced to believe that the savages had murdered them. Nor was he wrong in his conjecture. Some years afterward the blanched skeletons of the three were found by some hunters in the neighborhood of Warrior's Mark. The identity of the skeletons was proved by some shreds of clothing—which were known to belong to them—still clinging to their remains.

When Captain Blair's rangers, or that portion of them raised in Path Valley, came across to the Juniata, they had an old drum, and—it is fair to infer, inasmuch as the still-house then seemed to be a necessary adjunct of civilization—sundry jugs of whiskey accompanying them. At Jack's Narrows lived a burly old German, named Peter Vandevender, who, hearing the noise, came to his door in his shirt-sleeves, with a pipe in his mouth.

"Waas ter tuyfel ish ter meaning of all dish?" inquired old Vandevender.

"We are going to hunt John Weston and his tories," said one of the men.

"Hunt dories, eh? Well, Captin Plair, chust you go ant hunt Chack Hare. He ish te tamtest dory in Bennsylvania. He dold Weshton ash he would half a gompany to help him after he come mit ter Inchins."

What Vandevender told Blair was probably true to the letter; for one of the inducements held out to the tories to accompany Weston was that they would be reinforced by all the tories in the county as soon as the first blow was struck; but he was not raising a company. He was too cowardly to expose himself to the danger attending such a proceeding.

As soon as Vandevender had communicated the foregoing, the company, with great unanimity, agreed to pay Hare a visit forthwith. The drum was laid aside, and the volunteers marched silently to his house. A portion of them went into the house, and found Hare, while Blair and others searched the barn and outbuildings to find more of the tories. On the arrival of Captain Blair at the house, some of his men, in a high state of excitement, had a rope around Hare's neck, and the end of it thrown over a beam, preparatory to hanging him. Blair interposed, and with great difficulty prevented them from executing summary vengeance upon the tory. In the mean time, one of the men sharpened his scalping-knife upon an iron pot, walked deliberately up to Hare, and, while two or three others held him, cut both his ears off close to his head! The tory, during these proceedings, begged most piteously for his life—made profuse promises to surrender every thing he had to the cause of liberty; but the men regarded his pleadings as those of a coward, and paid no attention to them, and, after cropping him, marched back to Vandevender's on their route in search of Weston.

On their arrival at the Standing Stone, they communicated to the people at the fort what they had done. The residents at the Stone only wanted a piece of information like this to inflame them still more against Hare, and, expressing regrets that he had not been killed, they immediately formed a plot to go down and despatch him. But there were tories at the Stone. Hare soon got wind of the affair, placed his most valuable effects upon pack-horses, and left the country.

The failure of Weston's expedition, and the treatment and flight of Hare, compelled many tories, who had openly avowed their sentiments, to leave this section of the country, while those who were suspected were forced into silence and inactivity, and many openly espoused the cause of the colonies. Still, many remained who refused to renounce their allegiance to the king, and claimed to stand upon neutral ground. Those who had taken up arms against Great Britain, however, declared that there were but two sides to the question, and no neutral ground;—that those who were not for them were against them.

Hare was declared and proclaimed an "attainted traitor," and his property was confiscated and sold. Who became the purchaser we could not ascertain; but, after peace was declared and the treaty between the United States and Great Britain ratified, Hare returned, and claimed the benefit of that part of the treaty which restored their possessions to all those of his Majesty's subjects that had not taken up arms against the colonists. As there was no direct evidence that he killed Loudenslager, Congress was compelled to purchase back and restore his property to him.

He lived and died on his farm. The venerable Mrs. Armitage, the mother-in-law of Senator Cresswell, of Hollidaysburg, remembers seeing him when she was quite young and he an old man. She says he used to conceal the loss of his ears by wearing his hair long.

During life he was shunned, and he died unregretted; but, we are sorry to say, his name is perpetuated: the place in which he lived, was cropped, and died, and is still called Hare's Valley. The people of Huntingdon should long since have changed it, and blotted from their memory a name linked to infamy and crime.

57 Stories of Indian Capture and Torture