TORIES OF THE VALLEY — THEIR UNFORTUNATE EXPEDITION TO JOIN THE INDIANS AT KITTANING — CAPTAIN JOHN WESTON, THE TORY LEADER — CAPTAIN THOMAS BLAIR — CAPTURE OF THE BROTHERS HICKS — HANGING A TORY — NARROW ESCAPE OF TWO OF WESTON'S MEN, ETC.

A successful rebellion is a revolution; an unsuccessful attempt at revolution is a rebellion. Hence, had the Canadians been successful in their attempt to throw off the British yoke in 1837, the names of the leaders would have embellished the pages of history as heroes and patriots, instead of going down to posterity as convicts transported to the penal colonies of England. Had the efforts of the Cubanos to revolutionize the island of Cuba been crowned with success, the cowardly "fillibusteros" would have rated as brave men, and, instead of perishing ignominiously by the infamous garrote and starving in the dismal dungeons of Spain, they would now administer the affairs of state, and receive all the homage the world pays to great and successful warriors. On the other hand, had the revolution in Texas proved a failure, Burleson, Lamar, Houston, and others, who carved their names upon the scroll of fame as generals, heroes, and statesmen, would either have suffered the extreme penalty of the Mexican law, or at least occupy the stations of obscure adventurers, with all the odium which, like the poisoned shirt of Nessus, clings to those who are unsuccessful in great enterprises.

The same may be said of the American Revolution. If those who pledged their "lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor," to make the colonies independent of all potentates and powers on earth, had lost the stake, the infamy which now clings to the memory of the tories would be attached to that of the rebels, notwithstanding the latter fought in a glorious cause, endured the heats of summer and braved the peltings of the winter's storms, exhausted their means, and shed their blood, for the sacred cause in which they were engaged. For this reason, we should not attach too much infamy to the tories merely because they took sides with England; but their subsequent acts, or at least a portion of them, were such as to leave a foul blot upon their names, even had victory perched upon the cross of St. George. The American people, after the Revolution, while reposing on the laurels they had won, might readily have overlooked and forgiven weak and timid men who favored the cause of the crown under the firm conviction that the feeble colonies could never sever themselves from the iron grasp of England; but when they remembered the savage barbarities of the tories, they confiscated the lands of all who were attainted with treason, drove them from the country, and attached black and undying infamy to their names.

To some it may appear strange—nevertheless it is true—that, in 1777, the upper end of the Juniata Valley contained nearly as many tories as it did patriots. This is not a very agreeable admission to make by one who has his home in the valley; nevertheless, some of the acts of these tories form a part of the history of the time of which we write, and must be given with the rest. Let it be understood, however, that, as some of the descendants of those men, who unfortunately embraced the wrong side, are still alive and in our midst, we suppress names, because we not only believe it to be unprincipled in the extreme to hold the son responsible for the sins and errors of the fathers, but we think there is not a man in the valley now who has not patriotic blood enough in his veins to march in his country's defence at a moment's warning, if occasion required it.

The great number of tories in what now constitutes Huntingdon county may, in a great measure, be attributed to the fact, that, living as they did upon the frontier, they had no idea of the strength or numbers composing the "rebel" army, as they called it. They knew the king's name to be "a tower of strength;" and they knew, too, the power and resources of England. Their leaders were shrewd men, who excited the fears of the king's followers by assuring them that the rebels would soon be worsted, and all of them gibbeted.

The most of these tories, according to Edward Bell, resided in Aughwick, Hare's Valley, on the Raystown Branch, in Woodcock Valley, at Standing Stone, Shaver's Creek, Warrior's Mark, and Canoe Creek. They held secret meetings, generally at the house of John Weston, who resided a mile and a half west of Water Street, in Canoe Valley. All their business was transacted with the utmost secresy; and those who participated in their meetings did so under an oath of "allegiance to the king and death to the rebels."

These meetings were frequently attended by tory emissaries from Detroit, who went there advised of all the movements of the British about the lakes; and it is thought that one of these men at length gave them a piece of intelligence that sealed the doom of a majority of them.

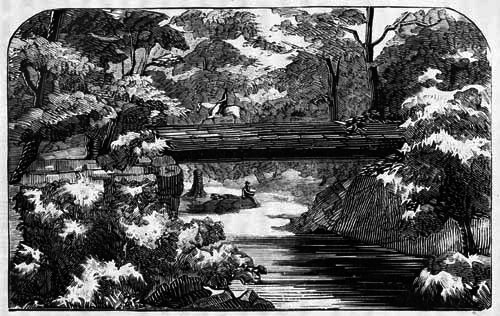

It appears that a general plan was formed to concentrate a large force of Indians and tories at Kittaning, then cross the mountain by the Indian Path, and at Burgoon's Gap divide,—one party march through the Cove and Conococheague Valleys, the other to follow the Juniata Valley, and form a junction at Lancaster, killing all the inhabitants on their march. The tories were to have for their share in this general massacre all the fine farms on the routes, and the movable property was to be divided among the Indians. It would seem, however, that Providence frustrated their plans. They elected John Weston their captain, and marched away in the dead of night, without drums or colors, to join the savages in a general massacre of their neighbors, early in the spring of 1778—all being well armed with rifles furnished by the British emissaries, and abundance of ammunition. They took up the line of march—avoiding all settlements—around Brush Mountain, and travelled through the Path to Kittaning. When near the fort, Weston sent forward two men to announce their coming. The savages, to the number of ten or twelve, accompanied the messengers; and when they met the tories, Weston ordered his men to "present arms." The order proved a fatal one; for the Indians, ever suspecting treachery, thought they had been entrapped, and, without any orders, fired a volley among the tories, and killed Weston and some eight, or probably ten, of his men, then turned and ran toward the town. The disheartened tories fled in every direction as soon as their leader fell.

Although these tories marched from the settlements under cover of night, and with the greatest possible caution, all their movements were watched by an Indian spy in the employ of Major Cluggage. This spy was a Cayuga chief, known as Captain Logan, who resided in the valley at the time,—subsequently at an Indian town called Chickalacamoose, where the village of Clearfield now stands. He knew the mission of the tories, and he soon reported their departure through the settlements. Of course, the wildest and most exaggerated stories were soon set afloat in regard to the number constituting Weston's company, as well as those at Kittaning ready to march. Colonel Piper, of Yellow Creek, George Woods, of Bedford, and others, wrote to Philadelphia, that two hundred and fifty tories had left Standing Stone, to join the Indians, for the purpose of making a descent upon the frontier,—a formidable number to magnify out of thirty-four; yet such was the common rumor.

The greatest terror and alarm spread through the settlements, and all the families, with their most valuable effects, were taken to the best forts. General Roberdeau, who had the command of the forces in the neighborhood, had left Standing Stone a short time previous, leaving Major Cluggage in command. The latter was appealed to for a force to march after Weston. This he could not do, because his command was small, and he was engaged in superintending the construction of the fort at Sinking Valley, the speedy completion of which was not only demanded to afford protection to the people, but to guard the miners, who were using their best exertions to fill the pressing orders of the Revolutionary army for lead.

Cluggage was extremely anxious to have Weston and his command overtaken and punished, and for this purpose he tendered to Captain Thomas Blair, of Path Valley, the command of all who wished to volunteer to fight the tories. The alarm was so general, that, in forty-eight hours after Weston's departure, some thirty-five men were ready to march. Twenty of them were from Path Valley, and the remainder were gathered up between Huntingdon—or Standing Stone, as it was then still called—and Frankstown. At Canoe Valley the company was joined by Gersham and Moses Hicks, who went to act in the double capacity of scouts and interpreters. They were brothers, and had—together with the entire family—been in captivity among the Indians for some six or seven years. They were deemed a valuable acquisition.

Captain Blair pushed on his men with great vigor over the mountain, by way of the Kittaning trail; and when he arrived where the path crosses the head-waters of Blacklick, they were suddenly confronted by two of Captain Weston's tories, well known to some of Blair's men, who, on the impulse of the moment, would have shot them down, had it not been for the interference of Captain Blair, who evidently was a very humane man. These men begged for their lives most piteously, and declared that they had been grossly deceived by Weston, and then gave Captain Blair a true statement of what had occurred.

Finding that Providence had anticipated the object of their mission, by destroying and dispersing the tories, Captain Blair ordered his men to retrace their steps for home. Night coming upon them, they halted and encamped near where Loretto now stands. Here it was found that the provisions had nearly run out. The men, on the strength of the reported destruction of Weston, were in high spirits, built a large fire, and passed the night in hilarity, although it was raining and exceedingly disagreeable. At the dawn of day, Gersham and Moses Hicks started out in search of game for breakfast, for some of the men were weak and disheartened for the want of food. These wood-rangers travelled three miles from the camp without anticipating any danger whatever, when Gersham shot a fine elk, which, in order to make the load as light as possible, the brothers skinned and disemboweled, shouldered the hind-quarters, and were ready to return to the camp, when five Indians suddenly came upon them and took them prisoners. They were again captives, and taken to Detroit, from which place they did not return until after peace was declared. These men unquestionably saw and experienced enough of Indian life to fill an interesting volume.

In the mean time, the company becoming impatient at the continued absence of the Hicks, several small parties were formed to go in search of them. One of these parties fell in with three Indians, and several shots were exchanged without injuring any person. The Indians took to the woods, and the men returned to the camp. The other party found the place where the elk had been skinned, and took the remains to the camp; the meat was speedily roasted and divided among the men, and the line of march again taken up. The certain capture of the guides, and the Indians seen by the party in search of them, induced the belief that a larger body of them than they wished to encounter in their half-famished condition was in the neighborhood, considerably accelerated their march.

The sufferings endured by these men, who were drenched by torrents of rain and suffered the pangs of hunger until they reached the settlements on the east side of the mountain, were such as can be more readily imagined than described. But they all returned, and, though a portion of them took sick, they all eventually recovered, and probably would have been ready at any time to volunteer for another expedition, even with the terrors of starvation or the scalping-knife staring them in the face.

The tories who, through the clemency of Captain Blair, escaped shooting or hanging, did not, it seems, fare much better; for they, too, reached the settlements in an almost famished condition. Fearing to enter any of the houses occupied, they passed the Brush Mountain into Canoe Valley, where they came to an untenanted cabin, the former occupants having fled to the nearest fort. They incautiously set their rifles against the cabin, entered it, and searched for food, finding nothing, however, but part of a pot of boiled mush and some lard. In their condition, any thing bearing resemblance to food was a god-send, and they fell vigorously to work at it. While engaged in appeasing their appetite, Samuel Moore and a companion,—probably Jacob Roller, Sr., if we mistake not,—who were on a hunting expedition, happening to pass the cabin, saw the rifles, and immediately secured them, when Mr. Moore walked in with his gun cocked, and called upon the tories to surrender; which peremptory order they cheerfully complied with, and were marched to Holliday's Fort. On the way thither, one of them became insolent, and informed Moore and his companion that in a short time they would repent arresting them. This incensed Roller, and, being an athletic man, when they arrived at the fort he fixed a rope to the tory's neck, rove it over a beam, and drew him up. Moore, fortunately, was a more humane man, and persuaded his companion to desist. They were afterward taken to Bedford; but whether ever tried or not, we have not been able to ascertain.

Captain Blair's men, while passing through what is now known as Pleasant Valley, or the upper end of Tuckahoe, on their return, paid a visit to a tory named John Hess, who, it is said, was armed, and waiting the return of Weston to join his company. They found Hess in his house, from which they took him to a neighboring wood, bent down a hickory sapling and fastened the branches of it around his neck, and, at a given signal, let him swing. The sight was so shocking, and his struggles so violent, that the men soon repented, and cut him down before he was injured to any extent. It appears from that day he was a tory no longer, joined the rangers, and did good service for his country. His narrow escape must have wrought his conversion.

The tories who escaped the fatal error of the Indians at Kittaning never returned to their former homes. It was probably as well that they did not, for their coming was anxiously looked for, and their greeting would unquestionably have been as warm a one as powder and ball could have been capable of giving. Most of them made their way to Fort Pitt, and from thence toward the South. They eventually all sent for their families; but "the land [of the Juniata Valley] that knew them once knew them no more forever!"

Captain Blair, whom we have frequently mentioned, soon after or about the close of the war moved to what is known as the mouth of Blair's Gap, west of Hollidaysburg, where John Walker now lives. He was an energetic man, and, by his untiring exertions, succeeded in getting a pack-horse road cut through his gap at an early day.

His son, Captain John Blair, a prominent and useful citizen, flourished for many years at the same place. His usefulness and standing in the community made him probably the most conspicuous man of his day in this section; and, when Huntingdon county was divided, his old friends paid a tribute to his memory in giving the new county his name.

MILL CREEK.